Historical Aspects to Political

Identity in the New York Basque Community

The majority of Basques in the organized New York Basque community have tended to prefer ethnic cultural events rather than political activities, and similar to other Basque Centers in the United States, the organizational statutes declare in writing that the Euzko-Etxea of New York is an apolitical institution. Still, the Basques in New York are the most politicized of any of the other communities of the United States. This additional layer in Basque identity results from several factors: the initial leaders of the first community tended to be Basque nationalists and this has self-perpetuated; the consistent Basque immigration to the city has brought current news regarding political developments; constant movement and travel of New York Basques to the homeland has allowed later generations to see first hand examples of dictatorship and these stories continued on to later generations; the history of the Basque Government-in-exile headquartered in New York facilitated exchange of ideas and personalized politics; and the regular access to an abundance of information and media reports in New York regarding current events in Euskal Herria affected the community. The dynamics of New York itself and New Yorkers surrounded with examples of diaspora politics influencing homeland politics -most obviously with the powerful Jewish community- and also with the impact of the location of the United Nations and easier access to politicians, have each played a significant role in increasing the political awareness of New York Basques.

|

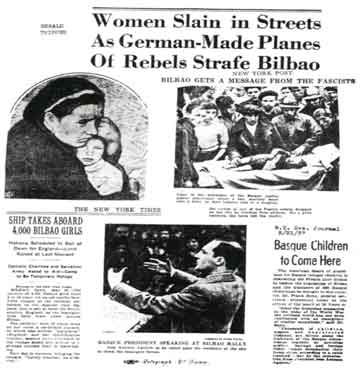

| Newspaper headlines about Basque children coming to USA |

For more than a century, a high percentage of Basque immigration to New York has been Bizkaian, perpetuated by chain migration. The majority of these Bizkaians’ families fought in Spain with the conservative Carlist forces, and later in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) with the republican military, and were mainly Basque nationalists. Those immigrants brought their political ideologies with them when they transplanted to New York and subsequently, reinforced the existing political opinions. It is also possible, however, that perhaps the immigrants chose to stay in New York and to associate with the existing Basque community as a result of its nationalist tendencies. Basques who did migrate to New York without these tendencies might have eliminated themselves from participating in the Centro Vasco-Americano activities, which focused on a nationalist definition of Basqueness, and conflicting opinions were therefore almost non-existent. In later years, children heard the stories regarding the dictatorship of Francisco Franco from their parents, then from their parents’ friends, then from other new immigrants ten years later, etc., and this reinforced the perception of Basques as victims of Castilian oppression, even for later generation Basques who had never visited or attempted to obtain unbiased information. They were surrounded with examples from their families and from hundreds of other Basques who had lived there and shared personal testimonies.

|

| Newspaper headlines about Gernika bombing. |

Political activity of early New York Basques

In 1920, several Basque individuals in New York collected private funds for the Basque Nationalist Party in the homeland, but the majority of members of the Centro Vasco-Americano did not get involved actively in homeland politics, and/or were barely making sufficient salaries to care for their own families and did not have extra money to donate for a political party. The 1923 beginning of the Spanish dictatorship of Primo de Rivera caused many Basques to flee in exile to the Americas. One of those was Elías de Gallastegui who moved to Mexico where he organized a Basque nationalist youth group and a branch of supporters for the Partido Nacionalista Vasco, PNV, Basque Nationalist Party. Gallastegui communicated to the Centro Vasco-Americano that he wanted to do the same in New York. When this was rejected by the C.V.A., a group of supporters broke away from the C.V.A organization and in 1926 formed a separate organization. They named it Aberria, or The Homeland, and continued with a pro-Basque nationalist agenda, and with their own newspaper Aberri. Aberri editor, Antón Osa, organized a Gallastegui visit to New York in order to gain attention and support for the PNV. Curiously, though the C.V.A. did not want to participate in any Gallastegui ventures, in 1935 it organized its own banquet commemorating Basque nationalism and its contemporary founder, Sabino Arana y Goiri. In 1937, Aberria joined forces with the Hispanic Confederated Societies until the end of 1938, when the organization disbanded and many individuals returned to join the C.V.A.

In the homeland, the Spanish monarchy fell in April 1931. The newly elected republican government promised to grant autonomy to those peoples who voted with a clear majority in favor of autonomy. On July 14,1931 in Estella-Lizarra, Nafarroa, the Basque people- through representative delegates- voted to proclaim their Statutes of Autonomy. The Republic required additional procedures of a majority of all municipalities voting yes, and all four of the provinces agreeing, and in addition a popular plebiscite of the four Basque provinces in order to obtain Basque Home Rule. Even after these conditions had been fulfilled, the Spanish Parliament still reserved the right to accept or reject the proposal. The Spanish Republican Parliament delayed their deliberations and Basque autonomy was finally approved on October 1, 1936, after the Spanish Civil War had already begun. President José Antonio Aguirre took his oath of office under the Tree of Gernika, on the site of the historical Basque parliament. However, after the Spanish military victories in the Basque provinces, the Basque Government went into exile.

The Basques in New York helped to establish the Pro-Euzkadi Committee in 1937, which had the duties to create and disseminate information about the current war situation in the Basque Country and to search for humanitarian aid for the refugees. The New York based Pro-Euzkadi Committee asked the C.V.A. for permission to utilize its office at 48 Cherry Street for their clerical work, and were granted permission. The C.V.A. also decided to mail information to all of its members, encouraging them to join the cause. The minutes of the February 1937 general meeting of the C.V.A. show that members stated “the Pro-Euzkadi Committee is conducting very important work for the needy of Euzkadi.” They immediately donated the profits from a December dance totaling $166.65, to the Pro-Euzkadi Committee. The same month the C.V.A. received letters from the Argentine Basque organization Zazpiak-Bat of Rosario in the province of Santa Fe, from the Department of Justice of the Basque Government, and from the Euzkadi Buru Batzara, or National Council of Euzkadi, which governed the PNV, and it is evident that the New York organization was participating in non-state international affairs with questions regarding the Spanish Civil War, refugee safety and placement, funding for a government-in-exile, and in an international network of information with other Basque communities.

Article 55 of the Centro Vasco-Americano legal charter read, “The President will not permit demonstrations on political or religious matters ... .” However, in December 1936, a general meeting of the membership unanimously approved the attendance and participation of the institution at a Madison Square Garden meeting of the Confederation of Hispanic Societies, set for January 5, 1937, to discuss the Spanish Civil War. They decided to send a delegation of twelve representatives, complete with a banner from the C.V.A., to participate in the meeting. The organization annually subscribed to the publication EUZKADI, a Basque nationalist newspaper, and it was available at the Social Building bar for members to read. In January 1937, the C.V.A. sent a congratulatory cable to the newly elected President of the autonomous Basque Country, José Antonio de Aguirre. Throughout the years, various Presidents represented the Centro Vasco-Americano at the meetings and activities of the Confederation of Hispanic Societies, not to plan social functions, but to discuss an anti-Franco strategy between Basque, Galician, and Catalan groups in New York. Basque President José Antonio de Aguirre was not only referred to as the “Basque Country President” in the C.V.A. announcements or minutes, but as “our President” in the recorded minutes, in speeches, and in printed bulletins.

It is interesting that the Basque association professed to be non-political yet they organized dinners to celebrate the father of contemporary Basque nationalist political ideology, Sabino de Arana y Goiri. Centro Vasco-Americano, C.V.A., co-founder and long time President Valentín Aguirre, who had demanded in strong language that the C.V.A. not allow any presentation of political matters, later proposed that the C.V.A. and its Board formally receive the Lehendakari of the Basque Government-in-exile and his wife upon their arrival in New York in 1941. Valentín Aguirre also collaborated with the Basque Government delegation and gave personal information about members, which was recorded in the C.V.A. ledgers, to the Basque Government-in-exile Delegates at their headquarters in Manhattan.

Diaspora understanding of the Spanish Civil War

The Basques living in New York during the 1930s would more than likely have had a collective political mentality that resulted from their parents and grandparents fighting in the Carlist Wars to protect the Basque fueros and traditional customs. They, or their parents, would have emigrated to escape the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. Now, their homeland was once again the target in a Spanish civil war and, what in today’s terms would be called, an “ethnic cleansing” by the Franco dictatorship. New York Basques had access to abundant print and radio reports on international affairs and were updated daily on events of the war. While Basques in the west relied on weeks-old letters and short sporadic newspaper articles covering far-off places of little interest to editors, the New York Times had its own correspondents writing daily from Spain and France.

|

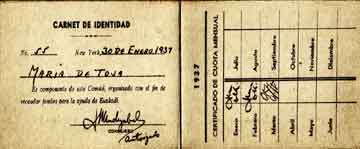

| Comite Pro-Euzkadi card of Mary Altuna Toja NY 1937 |

Dorothy Thompson published her regular column, “On the Record,” in the New York Herald Tribune, and on April 30, 1937, she wrote about the horror of civil war in Spain:

“For what is happening there is the ruthless, cold-blooded, vicious extermination of one of the rare peoples of the earth- the Basques. It is an extermination, which beggars every description of war, which violates every convention which has been set by man as an inhibition against his own ruthlessness for one hundred years or more. To sit by and not protest with all the breath in one’s body reads one out of the ranks of civilized and Christian society.”

She presented her readers with this description of the bombing of Gernika:

“The day is Monday. That is the marketing day in Guernica, when it is certain that the women with their children around them will be in the streets, in the market center of the town. First small parties of airplanes threw heavy bombs and hand grenade all over the town, choosing area after area in the most orderly fashion. The bombs tore holes twenty-five feet deep and brought down buildings over the heads of their inhabitants.”

“As the population scattered in panic the planes swooped low and opened machine gun fire on the running people, whether they were men women or children. […] As the people dove into cellars and under shelter the planes again flew high and dropped incendiary bombs, and the village flared with fire. And in the midst of this carnage men aloft saw priests kneeling by the dead and dying, administering extreme unction. Those fleeing were machine-gunned along the roads- women and children.”

“There is an oak in Guernica, which is called the tree of God. It has stood for 600 years, and from its stump new sprouts are shooting. The bombardment which racked away women and children and youths and old men never touched this tree. Under it the kings of Spain took oath to respect the democratic rights of Vizcaya and were answered with the oath of the Basques, pledging allegiance to the Señor, the Lord, but not the King of this province. For the Basques gave obedience to an equal, knowing that men must acknowledge leadership, but they gave subservience to no man. Were the spirit alive in that symbol still alive throughout the world, nations would not sit by meekly, but there would arise from all civilized countries, through their governments, a protest which even the Fascist dictatorship could not ignore. For, believe it or not, there are such things in the world as morality, as law, as conscience, as a noble concept of humanity, which, once awake, are stronger than all ideologies.”

Press coverage of events in Spain included headlines of The Herald Tribune: “Women Slain in Street as German-Made Planes of Rebels Strafe Bilbao”, the New York Post: “Bilbao get a Message from the Fascists”, The New York Times: “Ship Takes Aboard 4,000 Bilbao Girls”, and from the New York Evening Journal: “Basque Children to Come Here.” A large number of Basques in New York were from Bizkaia, and the news of Franco ordered bombings of civilians in their home towns and places they knew such as Durango, Gernika, and Bilbao, was overwhelming. In April 1937, communications between the various societies and organizations related in some way to Spain organized a joint dance to raise money for the hospitals of the elected Spanish Republican Government in Spain, and its fight against the Falangist forces of Franco. Lily Aguirre Fradua said, “We had dances and masses to raise money to give for the war refugees. We kids used to give our quarters.”

|

| Pro-Euzkadi card donations by Mary Altuna Toja NY 1937 |

The C.V.A. and its President, Florencio Laucirica, agreed to support a June 1937 petition from the American Board of Guardians for Basque Refugee Children, asking for moral support and collaboration in their plans to rescue five hundred Basque children from war in Bizkaia, and to bring them to the United States. An “Extraordinary General Meeting” was called for the entire membership of the Centro Vasco-Americano society, and a commission of twenty-seven members headed the organization and collaboration plans. They also asked for the specific rules and regulations for Basque families who might wish to adopt any of these children. Pedro and Mary Altuna Toja kept one of the flyers, which included information with newspapers articles titled, “500 little Basque refugees coming to the U.S.A.”, “Food and Peace for little War Victims”, “Liner being Chartered to Bring Basque Children”, and “Washington May Admit 500 Basque Children on Visitors’ Visas Granting Six-Month Stays.” The New York Evening Journal reported on May 21, 1937 that the American Board of Guardians for Basque Refugee Children, headquartered in New York, had chartered the French liner Sinaia to hasten the evacuation of Bilbao and the eventual transport of 500 Basque children to the United States. Board members included Dr. Frank Bohn, Dean Virginia Gildersleeve of Barnard College, Professor James T. Shotwell of Columbia University, Mary E. Woolley, president emeritus of Mount Holyoke College, and Representative Carolyn O’Day of New York; Dorothy Thompson and Albert Einstein also were leaders, and Eleanor Roosevelt accepted the position of Honorary President. The original plan was to have the children disembark at Donibane Lohitzun-St. Jean-de-Luz, in the northern Basque Country, then take them by train north to Paris, and to board the President Harding at Le Havre, with the expected arrival in New York on June 19, 1937. Older children were to be placed in homes, and the younger children were to stay together under the tutelage of the Basque priests and teachers that would accompany them to a large nursery home to be established in New York City. Another group, the Committee for German-American Relief for Spain, was established at the same time in New York, “To redeem the honor of Germany and the humanitarian tradition of the German people, decimated by Hitler’s aviators in their massacre of the Catholic civilians of Guernica,” stated Dr. Jacob Auslander, Chairman of the committee.

When 2700 families immediately responded offering their homes and families and the necessary money to care for and possibly adopt the Basque children, the American Board asked permission to bring 2000 children instead of the 500 previously sought. However, the leadership of the Catholic Church, and specifically Cardinal O’Connell of Boston, expressed their opposition to allowing the children into the United States. Soon after, Eleanor Roosevelt stated in a press conference that perhaps it was not such a good idea to being the children to the United States, so far away from their homeland, and by June 25, 1937 the U.S. State Department systematically denied all visa requests for the Basque refugees and orphans (San Sebastián 1991:25).

The C.V.A. maintained communications with the Basque Government while it was headquartered in Valencia in the summer of 1937. The “Collector” of the C.V.A. dues, José Altuna was directed at a membership meeting to share the books, letters, and documents sent by the Basque Government with all of the Basque families and persons he visited when collecting fees. In October 1937, the organization decided to buy and display both an ikurriña and a United States flag at the Social Building, and the ikurriña arrived from Bilbao a few months later. Assorted individuals, such as Pedro and Mary Toja, also privately received information bulletins from the Basque Government General Delegation, headquartered in Barcelona after the fall of Bilbao in 1937. Information from the homeland Basques to family members in New York also came in personal written communications and in verbal messages sent with other immigrants from their own village.

The Sociedad Española Nacional de Socorros Mutuos, Spanish National Benevolent Society, also known as La Nacional, The National, was founded in New York in 1868, and during the Spanish Civil War had relations with the Spanish Republican Government. In 1938, the Spanish Benevolent Society invited the Centro Vasco-Americano to attend meetings regarding the unification of their societies, but the C.V.A. declined the offer. They continued collaborating together for activities, and also cooperated with the Unidad Galicia, Unity Gallega of the U.S., Incorporated, but had no intention of combining organizations with either. The Basques preferred their organization remain separate from other ethnic groups from Spain, and to choose to conduct their own communications with other Basque communities around the world.

In 1938, Vidal Mendizabal wrote a letter on behalf of the C.V.A. to the Basque Delegation in Mexico City, asking for information about their activities in support of needy Basques exiled from the Basque Country. While several members were ready to begin a collection for those exiles, others intervened and suggested that the club not get involved in any gathering of funds that would not be specifically for the C.V.A. The meeting minutes do not name who was opposed the collections, but it is odd that, abruptly, the organization would move to such an extreme, from promoting the evacuation and care of 2000 children in New York and hosting dances and masses to raise money for war victims, to agreeing to only organize collections that specifically helped their own organization. It could be that the political leanings of members and leaders were changing; the elected leaders had not changed, but perhaps the type of members attending the meetings and voting had changed; or perhaps they had received word that the Basque Government would soon have its own Delegation right in Manhattan. The arrival of the Basque President’s representatives coming to establish a Delegation of the Basque Government marked the beginning of the contemporary politicization of the New York Centro Vasco-Americano membership and the larger Basque community. Their influence changed the trajectory of Basque identity development in New York, which still remains significantly more interested and more aware of politics in Euskal Herria.

|

Sources:

Legarreta, Dorothy.1984. The Guernica Generation: Basque Refugee Children of the Spanish Civil War. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

San Sebastián, Koldo. 1991. The Basque Archives: Vascos en Estados Unidos (1938-1943). Donostia-San Sebastián: Editorial Txertoa.

Totoricagüena, Gloria. 2003. The Basques of New York: A Cosmopolitan Experience. Serie Urazandi.Vitoria-Gasteiz: Eusko Jaurlaritza.

Totoricagüena, Gloria. 2003. La Diáspora Comparada: Identidad, Cultura, y Política en la Diáspora Vasca. Serie Urazandi.Vitoria-Gasteiz: Eusko Jaurlaritza.

euskonews@euskonews.com