Artetsu Saria 2005

Artetsu Saria 2005

Arbaso Elkarteak Eusko Ikaskuntzari 2005eko Artetsu sarietako bat eman dio Euskonewseko Artisautza atalarengatik

Buber Saria 2003

Buber Saria 2003

On line komunikabide onenari Buber Saria 2003. Euskonews y Media

Argia Saria 1999

Argia Saria 1999

Astekari elektronikoari Merezimenduzko Saria

The behavior during the breeding period depends on the sex of the woodcock. If male the bird will be roding,1 trying to mate females. If female, after mating with a male, the bird will be nesting.

The Eurasian woodcock is distributed throughout Eurasia (Shorten 1974; Cramp and Simmons 1983). Its distribution range (Figure 1) extends from approximately 45º N to 65º N and from the Atlantic cots of Ireland to the Pacific coast, as far as 160º E.

The woodcock which visit us is present during all or part of its annual cycle in all the countries of the Western Paleartic.

Its breeding area, stricto sensu, includes in Europe: Fennoscandia, the Baltic countries, the countries of Central Europe, Russia, Byelorussia, Ukraine, and the countries of Caucasus.

Figure 1: Eurasian woodcock’s distribution.

The wintering area, sticto sensu, is situated in Europe/Africa mainly in Portugal, and around the perimeter of the Mediterranean: parts of the Spanish State, Italy and Greece; the coasts of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Israel; an inner part of Jordan; the north of Egypt and Libya; the coastal fringes of the Maghreb countries; and Iran (south fringe of the Caspian Sea). It is also strictly wintering in the western parts of Ireland, England and France.

An intermediate area, situated between the strict breeding area and the strict wintering area, is home to the woodcock through the year, including most parts of the United Kingdom, most parts of France, Belgium, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Denmark; and west parts of Caucasus.2

It seems that there would be a genetic diversity3 between the different woodcock population groups (Burlando et al. 1996).4

From February to August, the male flies at dusk and at dawn (Estoppey 1988, Marcströn 1994). These flights, accompanied by song, make up a display, termed roding. The main purpose of roding is to find females. At this time of day observation is easy and does not cause disturbance. It is estimated that a male rodes over some 300 hectares during the season. Several males are roding the same area. A male can mate with several females. The male and female only stay together for 3 or 4 days.5 Then the male restarts his roding flights.

Some one-year-old males engage in roding routines with no evidence that they have mated with a female.

Only the female woodcock sits on the eggs. The incubation period is between 21-22 days.6 The young are able to fly at the age of about 20 days.7

The females can breed in their first year of life (Ferrand and Gossmann 2001).

(In our experiments, Trasgu (in 2006) and Navarre (in 2007) were nesting in their first year of life: both of them were young females. In 2008, Navarre has become an adult woodcock.)

Regarding the possibility of second nesting, Ferrand and Gossmann (2001) write: “A second lay in the same season after a successful first brood has never been observed. Nonetheless, observations of nesting females surrounded by her young suppose that thus does happen.”

Up to our first experiment in 2006, most of the knowledge about woodcocks has been gathered through ringing and/or via conventional radio-telemetry.

Here some interesting conventional radio-telemetry experiments to be underlined, since they can give us a clue to better understand the behavior of the different woodcocks in our own experiments.

5.1. Roding

Information gained in 1978 from radio-tagging 10 males and two female woodcocks (Hirons 1980) confirms that roding areas are not exclusive and that the real purpose of the male woodcock’s roding behavior is to find or attract females with which to mate.

The radio-tagged males did not maintain exclusive territories either for roding or for feeding. “The areas over which seven of the marked birds were observed to rode overlapped considerably...” (Hirons 180, p. 351)

Hirons and Owen (1982) equipped 70 woodcocks with transmitters from March to July each year from 1978 to 1980 in Whitwell Wood, Derbyshire. According to these authors:

(1) At dusk and dawn trough the long breeding season (in Britain, late-February to mid July) roding woodcocks make extensive flights above the woodland canopy, calling repeatedly.

(2) Woodcocks fitted with transmitters have molted, roded, mated, laid eggs and reared broods.

(3) After radio tagging most birds undergo a period of ‘adjustment’ lasting from one day to a week.

(4) A high proportion of males return each year to display over the same area.

(5) Male woodcock are successively polygynous.

(6) They do not defend either an exclusive or specific area to which females are attracted, and in which mating and/or nesting tales place.

(7 )Males display solitary over large areas, often over 100ha in extension. These may overlap completely the areas over which other males rode.

(8) Individual males have been recorded displaying over points 3 km apart on the same evening.

(9) Roding males are seldom continuously in the air for more than 20 minutes (maximum yet recorded 43 minutes) before resuming display flights.

(10) Most birds display for about twice as long in the evening as in the morning and the maximum time spent roding by a radio tagged male in a 24 hour period has been 64 minutes.

(11) Radio tagged birds have displayed throughout the entire breeding season (i.e. over four months)8.

(12) When a male finds a receptive female he remains with her constantly (usually 3-5 days) before resuming display flight.

(13) The frequency of such non-roding periods during the breeding season can be used as a measure of each individual’s ability to locate mates (from none to at least four females per season for males studied).

(14) Variation in the success of individual males in locating (and presumably mating) with females can thus be related to differences in the timing and duration of their display periods (see Figure 2).

(Figure 2)

(15) The success of male woodcocks in locating mates in relation to the length of time spent displaying. For each day interval the average time spent displaying per evening by males which located a mate in that period (circles) is compared to the time displaying by those that did not (triangle). The figure is based on over 120 observations of 14 individual males and 13 recording mates.

Hoodless et al. (2007) write that,

a) Roding flights of individual birds seldom last more than 20 min and typically 2-4 separate flights are made each evening (Hirons and Owen 1982). The roding areas of several males often overlap (Hirons 1980).

b) The differences in the roding activity of individual males identified in this study agree with the work of Hirons (1980,1983), who suggested that roding woodcocks establish a dominance hierarchy whereby one or two dominant males rode for longest each evening at a site and obtain most mating with females.

c) Hirons’s observations were based on a radio-tracking study at a single location and our results indicate that the hierarchy of activity between males is a common phenomenon and not imply restricted to high-density populations.

d) The proportion of non-roding males may vary between sites or years and to some extent buffer change in the size of the breeding woodcock population.

Hirons (1980) writes that two breeding females were also fitted with transmitters.9 “Woodcocks fitted with transmitters have roded, mated and laid eggs” (p. 351).

Furthermore, “... when a radio-marked female lost her clutch (...) was accompanied 36 h later by a radio-marked male. Similarly, a radio-tagged female was flushed with a second bird only 24 h after losing her brood and then on several subsequent occasions before she relaid 12 days later” (p. 353).

According to Hirons and Ownen (1982):

(1) Females breed in their first year but many first-year males do not display or take part in breeding.

(2) Lost clutches and sometimes broods are rapidly replaced.10 (Males do not incubate or accompany broods.)

(3) Females almost invariably change woods between breeding attempts (a 10 km movement being the farthest recorded).11

(4) Regularly locating the broods of radio tagged females has shown that chicks can fly when 21 days old but continue to be accompanied by their mother about another 17-18 days.

Hirons (1988) writes that, “... Radio-tracking studies of females show that females select their future nest site in areas which have utilized intensely for the period prior to egg-laying...”

(Our experience in 200612, 200713 and 200814 confirms this selection of the nest site: before nesting the birds intensely utilized their nesting areas.)

Trasgu in 2006:

Possible nest: around May 25th.

Navarre in 2007:

Number 88 refers to the Argos’ ID. Nest: around May 30th.

Navarre in 2008:

Nest: around May 30th.

Navarre in 2007 and 2008:

Navarre’s position on May 30th: around 2.8 Km from last year’s nest.

Maximum dispersion among all the different positions close to the nests given by Navarre in 2007 and in 2008.

We have been tracking woodcocks via satellite with PTTs developed by Microwave Telemetry Inc (MTI) since 2006: in 2006 with a young female; in 2007 with a young female and another young, without knowing if it was male or female; in 2008 with an adult female; and also in 2008 with two males, both young.15

What follows is a sketch which will reach some interesting conclusions.

6.1. Our experiments about nesting: 2006, 2007 and 2008

(a) Data in 2006:

Trasgu was equipped with a PTT-100 12 gram solar PTT (duty cycle: 48/10 and transmission interval (TI): 60 seconds).

Trasgu gave an emission on May 25th (a LC 2 location), then no datum up to May 30th (a LC Z location) and then no datum at all up to June 16th (with a LC 3 location). Trasgu was in her possible nest from May 27th to June 16th without emitting. (This is why we think the bird was a female.)

After June 16th the bird gave no emission at all.

So, her nesting period can be taken from May 25th to June 16th.

(b) Data in 2007:

Navarre was equipped with a PTT-100 9.5 gram solar PTT (duty cycle: 48/10 and transmission interval (TI): 45 seconds).

Navarre gave an emission on May 22nd (a LC B location), then no datum up to May 30th (a LC 0 location) and then again no datum up to June 11th (with a LC 0 location).

After June 11th the bird gave emissions in Russia up to September 24th.

So, her nesting period can be taken from May 22nd to June 11th.

(c) Data in 2008:

Navarre’s second nesting. Navarre gave an emission on May 30th (a LC 2 location), then no datum up to June 4th (a LC Z location) and then again no datum up to July 9th (with a LC Z location).

After July 9th the bird gave some emissions in Russia, starting on July 17h.

So, her nesting period can be taken from May 30th on.

It is clear that Navarre has been, without any doubt at all, nesting during the whole period. Where was she after that? No idea at all; maybe she was with her chicks during some days.

6.2. Our experiments about roding and mating: 200816

Laguna and Araba have been ‘missing’ during some few days,

when they were in Araba (Basque Country) and in the breeding zone. Were

they roding? Mating females?

Can be related those missing days to mating after roding? It is really difficult

to give a right answer, but we will try to see all these ‘missing’

days, and, as hypotheses, try to relate those data with possible mating

periods.

(Both woodcocks were equipped with two special PTT-100 9.5 gram solar PTT, with a new technology developed by MTI.)

(a) Araba’s data (young woodcock):

While Araba was in Araba (Basque Country), here the dates when the bird was missing:

March 29th (a LC Z location) to April 1st. From April 6th to April 11th and then from April 11th to April 16th.

While Araba was in Russia, the bird has no missing days.17

(b) Laguna’s data (young woodcock):

While Laguna was in Araba (Basque Country) the bird was missing during the following dates:

March 17th to March 22nd.

While Laguna was in Russia, here his missing days:

From June 8th to June 13th; from June 24th to 29th; from July 4th (a LC Z location) to July 10th; from July 31st (a LC Z location) to August 5th and from August 10th (a LC Z location) to August 16th (two LC Z locations) and then to August 24th (a LC location).18

Again, we must underline that all these data are related to dates where the birds were missing. Missing to mate females?

Taking into account the specific technological characteristics of these two PTTs, which are able to be charged in very difficult environments, it can be plausible that during the above mentioned dates19 both birds could have been first roding and then mating females.

Bibliography

Burlando, B. et al. (1996) A study of the genetic variability in population

of the European woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) by random amplification

of polymorphic DNA. Ital. J. Zool., 63: 31-36.

Cramp, S. & Simmons, K.E.L. (1983) Scolopax rusticola Woodcock, in Cramp, S. & Simmons, K.E.L. (ed.) The birds of the western Palearctic. Vol. III: 444-457. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Estoppey, F. (1988) Contribution a la biologie de Bécasse des bois (Scolopax rusticola L.) dans le Jorat (Vaud, Suisse) par l’observation de la croule vespérale, Nos Oiseaux, 39: 397-416.

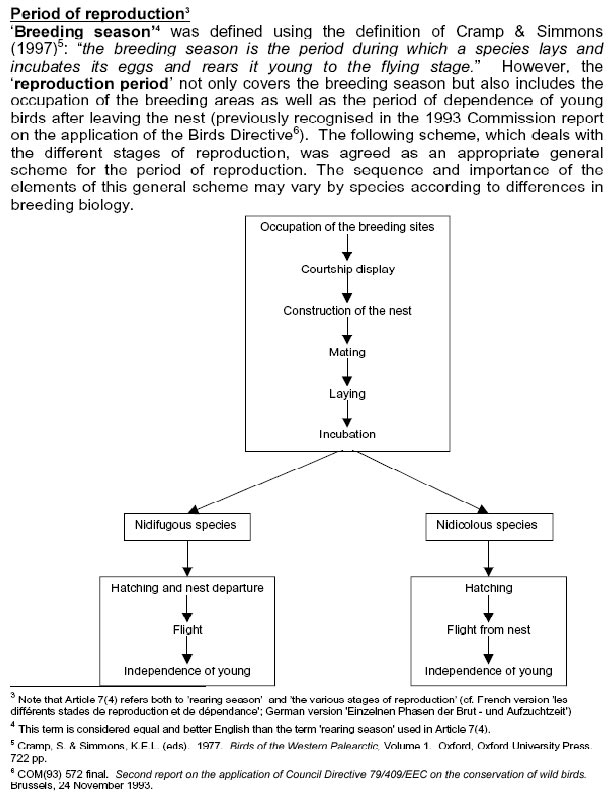

European Commission (2001) Key concepts of Article 7 (4) of Directive 79/409/EEC. Period of reproduction and prenuptial migration of Annex II Bird Species in the EU.

Ferrand, Y. and Gossmann, F. (2001) Elements for a Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) management plan. Game and Wildlife Science, Vol. 18 (1): 115-139.

Hirons, G. (1980) The significance of roding by woodcock Scolopax Rusticola: an alternative explanation based on observations of marked birds, Isis, 122: 350-354.

---------- (1983) A five study of the breeding behaviour and biology of the Woodcock in England –a first report, in H. Kalchreuter (ed.) Proceedings of the second European and Snipe Workshop, Slimbridge, UK, IWRB: 51-67.

---------- (1988) Habitat use by Woodcock (Scolopax Rusticola) during the breeding season, in Proceedings of the Third European Woodcock and Snipe Workshop, IWRB, Paris, 42-47.

Hirons, G. and R. B. Owen (1982) Radio tagging as an aid to the study of woodcock, Symp. Zool. Soc. London, 49: 139-152.

Hirons G. and T. H. Johnson (1987) A quantitative analysis of habitat preferences of Woodcock Scolopax rusticola in the breeding season, Isis, 129: 371-381.

Hoodless, A. N. et al. (2007) Vocal individuality in the roding of Woodcock Scolopax rusticola and their use to validate a survey method, Isis, 150:80-89.

Marcströn, V. (1994) Roding activity and woodcock hunting in Sweden, in Forth European Woodcock and Snipe Workshop, H. Kalchreuter (ed.), IWRP, 31: 55-60.

Shorten, M (1974) The European Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola). A Search

of the Literature since 1940, Game Conservancy report nº. 21.

Fordingbridge: The Game Conservancy.

Snow, D.W. and Perrins, C.M. (1998) The birds of the Western Palearctic.

Concise edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

This work is based on the different projects performed by the CCB (Club de Cazadores de Becadas) since 2006 up to 2008. The projects have been sponsored by the Government of Navarre (2006, 2007, 2008), the Government of Catalonia (2006) and Microwave Telemetry Inc (MTI) (providing two prototypes with a new technology in 2008); also by the CCB itself (in all these years).

Here some of the people we would like specially to thank:

(a) The Navarrese team (Isabel Leranoz, Alfredo Beloki and Jose Inazio Urriza) and the Araba team (brothers Asier eta Rubén San Vicente, Josu Salazar, Victor Regueiro, Javier Uriarte and Ikatz Pérez de Arriba).

(b) Dr. Charles Fadat and Dr. Nikita Chernetsov gave very helpful information.

(c) Jonathan Rubines used genetic analyses to know the sex of our woodcocks.

(d) The friends of Argos always have been ready to help: Maura Massana, Anne Marie Breonce, Aline Duplaa and Bill Woodward.

(e) Last but not least, special thanks to the whole team of Microwave Telemetry Inc (MTI), to Cathy Bykowsky, and mainly to Paul Howey.

(*) This work is part of a series of different papers done by a team composed by Ibon Telletxea, Mikel Arrazola, Zarbo Ibarrola, Raúl Migueliz, Joakin Anso, Izaskun Ajuriagerra, Ruben Ibáñez, Roberto Gogeaskoetxea, Felipe Diez and Joseba Felix Tobar-Arbulu.

1 In French, the word croule is used.

2 See also http://www.woodcockireland.com/mngt_plan.doc.

3 Jonathan Rubines is writing a doctoral thesis on that topic, i.e., the possible genetic diversity among woodcock populations.

4See Key concepts of article 7(4) of Directive 79/409/EEC, September 2001.

5In http://www.kynigos.net.gr/becatsa/english/bio.html; see also Ferrand and Grossman (2001) p. 117. According to Hoodless et al. (2007), woodcocks are highly secretive when nesting and their cryptic plumage means that they are rarely seen. However, males perform conspicuous display flights, a behavior known as ‘roding’, over the woodland canopy at dawn and dusk as they search for receptive females.

6 According to some authors the incubation period is 21 to 24 days: http://www.woodcockireland.com/mngt_plan.doc.

7 According to Snow and Perrins (1998), fledging period is c. 15 to 20 days; but sometimes chicks are able to get off ground at 10 days: http://www.woodcockireland.com/mngt_plan.doc.

8 Remember that this experience was made in the United Kingdom.

9 According to Hirons and Jonhson (1987), during April and May 1985 ten woodcocks were equipped with transmitters: seven nests were located by a combination of searching and the use of trained dogs.

10 Hirons and Owen say that two females that lost broods (two and ten days after hatching respectively) began incubating replacement clutches only 12 days later.

11 See our experience with Navarre.

12In Basque see http://www.euskonews.com/0380zbk/gaia38002eu.html and http://www.euskonews.com/0383zbk/gaia38302eu.html; in Spanish see http://www.euskonews.com/0380zbk/gaia38002es.html and http://www.euskonews.com/0383zbk/gaia38302es.html; see also http://www.microwavetelemetry.com/newsletters/spring_06page7.pdf.

13 In Basque see http://www.euskonews.com:80/0431zbk/gaia43102eu.html and http://www.euskonews.com/0433zbk/gaia43302eu.html; in Spanish see http://www.euskonews.com/0431zbk/gaia43102es.html and http://www.euskonews.com/0433zbk/gaia43302es.html; see also Les Voyages d’Astur et de Navarre, Bécasse Passion, 2007, 62: pp. 16-22.

14 See http://www.microwavetelemetry.com/newsletters/spring2008page6.pdf; see also Navarre, suivie par Radio Télémétrie... 760 Km parcourus, Bécasse Passion, 2008, 65, p. 11; and the forthcoming papers in www.euskonews.com: Burdinazko oilagorra urrezko bilakatu da (in Basque) and La becada de hierro se ha convertido en becada de oro (in Spanish).

15 The genetic analyses in 2007 and 2008 to know the woodcocks’ sex were performed by J. Rubines.

16 In a forthcoming paper in www.euskonews.com (in Basque: Mugarik gabeko Scolopax Rusticola: teknologia berria; and in Spanish: Scolopax Rusticola sin fronteras: nueva tecnología) we will deal with the experiment performed this year (2008) using two prototypes with a new technology developed by MTI.

17 Araba gave his last emission on August 12th, (data up to September 9th).

18 Laguna gave his last emission on August 24th, (data up to September 9th).

19 This does not mean, of course, that these missing days were the only days where the males were possibly mating females. Furthermore, if we consider that the special duty cycle of the new PTTs is 55/8.